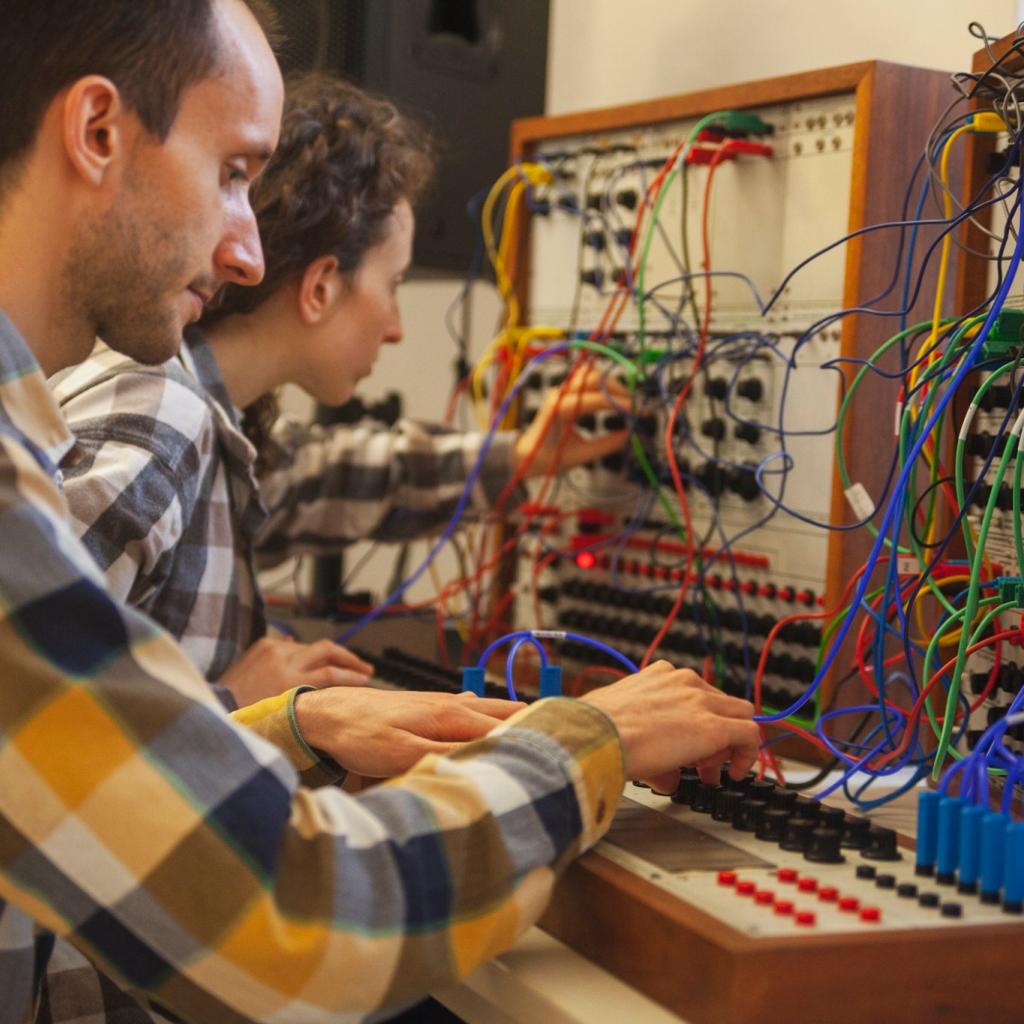

Interview with the artists Nicoletta Favari and Christopher Salvito

In January and February, Nicoletta Favari and Christopher Salvito were in Krems as artists-in-residence and not only worked with Ernst Krenek’s Buchla synthesizer, but also on Krenek’s Schweighofer concert grand piano from Ernst Krenek’s legacy in the Ernst Krenek Forum.

Alethea Neubauer spoke with them about their careers, the work with the unusual sound machine, and about their new projects.

Could you tell us about your musical backgrounds?

Christopher: As a duo we have been active since 2015. We met at a music festival and both have backgrounds in classical music. Nico is a pianist and I’m a percussionist. We have been working together ever since focusing on contemporary music and experimental music, at first playing compositions by many different composers and later starting to write our own pieces.

Nicoletta: I started playing the piano when I was very young. I studied the piano in Italy and Scotland, where I did my masters. Christopher played many different instruments and arrived at percussion when he was 17 years old. He studied in the States.

So, you have been working together since 2015 with your duo “Passepartout”. What is the focus of your music?

Christopher: The focus is always changing, but it’s always about reconsidering the way people listen to music or connect with music. That can mean a lot of different things. It can be electronic and experimental. It can be an installation, or it can be some kind of visual artwork that is linked to music. It could also be a collaboration with an artist of a different discipline. The thing that ties it all together is sound.

Nicoletta: The experimental and innovative aspect is essential for our music and proposing experiences for people to interface with the world through music.

Christopher: Everything we are doing is its own complete world. Right now, we are focusing on the Buchla synthesizer, but another time it could be something completely different.

I’ve seen your project “Sound Envelopes”. Do you create all this by yourself, also the hand crafting?

Christopher: We try to do everything ourselves. In the case of that project though, we always try to work with a local artist who makes the prints on the outside, but we make the device.

Nicoletta: We’re always traveling a lot, so it is very important for us to be as independent as possible in everything we do.

How did you get in touch with electronic music?

Christopher: We have only been thinking about electronic music much only recently, even though it has been a very important part of our work since the beginning. I think we were never thinking about it as electronic music before. The music we were making, always just had electronics in it.

Nicoletta: We started with the normal repertoire for piano and percussion, but there is not so much for this specialized instrumentation. Whatever we found, we had to play, and a lot of it contains electronics.

Christopher: Also, the first very big classical piece for this instrumentation is “Kontakte” by Stockhausen. We’ve never played that piece, but it has set the course for this instrumentation and I think many composers look back at it when they write their pieces.

Nicoletta: In the beginning our use of electronics was basically just tapes, so fixed media. Then it progressed to Max patches and we started working with other people who build Arduino-based [an open-source physical-computing-platform] things too.

Christopher: More than a year ago we started building our own instruments too. First, we built acoustic and electroacoustic instruments with simple amplification. By that time, we had written a complete set of music using them, and we combined those instruments with the laptop. The laptop had a big role in the pieces. That led us to think, if we wanted to take more control over this aspect of our work, we needed electronic instruments. Since then, it has been a more inside look at electronic music and how it works. We started focusing on it more seriously from there.

What fascinates you about working with synthesizers and electronic music?

Nicoletta: It is an endless world. Right now, we are interested in working specifically with analog synthesizers and we think that they have a special value. Every synthesizer has such a unique voice and character. It’s also fascinating, but maybe also frustrating sometimes, for a listener to hear a sound without knowing what the source is. The performative aspect of electronics is essential for us, and the acoustic part has stayed important to us too. If we are working with the synthesizer, maybe I’m on the keyboard and the synthesizer and Chris is playing percussion, or Chris is on the synthesizer and I’m on the piano.

Christopher: It’s also fascinating that it is very fundamental, like kind of going to the most basic essence of something. What I still find attractive about percussion, is how simple and visceral it is. Everybody understands what I’m doing as a percussionist. You hit something and it makes a sound. It is as simple as it can be. I think when you start dealing with electronics, things can become kind of esoteric and difficult to understand, especially as an audience member. If you are building analog instruments, and they are an older more fundamental version of the way the sounds are made, then it gets to that simpler more visceral basis. This perspective really changed the way we think about music and sound, because even if we thought we understood what was happening on the laptop, our understanding is more developed now.

Nicoletta: And we can control the instruments and act on them. It’s a different kind of relationship than to the laptop.

Christopher: Thinking about synthesizers as instruments for performers, rather than for the studio, is really an interesting topic - and Don Buchla thought a lot about that.

What do you like about working with the Buchla synthesizer?

Christopher: It’s been amazing.

Nicoletta: It is our first encounter with the Buchla. It’s really fascinating to see how an instrument becomes an interface with the world. At the same time the question comes up: Is the music interface shaping your mind and your music making or are you making the music interface. This feedback is interesting. It’s amazing that one person built this instrument about 55 years ago which has shaped the music making of so many people for so many years.

Christopher: Some parts of the Buchla are so familiar and even seem identical to anything you find on any synthesizer today, which is amazing - it shows how innovative the instrument was. However, it has its own elements that marks it clearly as a different species.

And what is very different?

Christopher: The keyboard on the right cabinet for example is like a touch controller, but it doesn’t work like you would expect from a keyboard, instead it’s more like a touch-controlled mixer. I’ve never seen anything like that yet.

Nicoletta: When looking at the two cabinets and the types of modules, it becomes clear that Krenek chose them according to his own needs. He had something in mind. So, it is quite a challenge to try to make your own thing without considering this thumbprint of Krenek and Buchla.

Was your first contact with the Buchla intuitive? Did you have difficulties when starting off?

Christopher: I found it very intuitive and very simple in a way. It is an older version of synthesizers, and so there isn’t too much to keep track of and learn from zero. I think I would have had more troubles if it were very new.

Nicoletta: We didn’t really have any particular problems, but I think it’s also because we don’t plan a live performance. It would be harder in that case because even though Buchla is saying it is a performance instrument, this specific Buchla… I’m not sure [laughs].

Christopher: If you wanted to give a 40-minute-long concert and you needed a big diversity of material, it’s very hard with just one patch, you’re limited in changing things. For us, it’s been easier to make one shorter piece and then make another short piece with time to re-patch in between.

Do you record everything, and do you improvise? How is your approach?

Nicoletta: We have two different projects, and they have differing approaches.

Christopher: One project is for Buchla and piano which we’ve just finished right now. We’re going to release a small album. First, we came from the perspective of Krenek’s piece “Tape and Double”. It was very interesting to hear it for the first time, and now it’s quite interesting to go back to it and listen again. After working with the Buchla a bit, we can now identify its unique sound in that recording. One thing we noticed about that piece is this kind of call-and-response that’s consistent throughout the work - the electronics will do something, and then the piano will respond with a similar texture. I was thinking that maybe that has a lot to do with the time and the technology. It would have been harder to make things happen completely in unison then. But it’s easy today because we have software that makes it very simple to follow along. Because of that, we wanted to do something where the piano and the Buchla play almost exclusively in unison with different textures. We found a patch over some days, and from it we formed different characters and ideas.

I wouldn’t really call it an improvisation. First, we just recorded the Buchla part on its own, and once we were happy with how that part sounded, we transcribed what we heard the synthesizer doing. Then, Nico played those parts on the piano. We were also using some kinds of preparation and extended techniques to make the piano sound a little bit more electronic and to bring it into the world of the Buchla.

Nicoletta: It was also a bit of a challenge. Buchla said that he made the synthesizer because he didn’t like what the piano keyboard was offering. It was too limited. Of course, in 2021 so much music has been written for the piano, so it’s difficult to find any new ideas. By starting from the synthesizer and then looking at the piano through that filter, new things can be found.

Christopher: Yes, it made us think in a completely different way because we’re having the forms and development of the piano be dictated by this really different kind of system. It’s very hard to write for the Buchla the way you would write for a piano, notate some notes out and try to produce them.

How do you notate the Buchla sounds?

Nicoletta: At first, we tried to pass it through a pitch analysis software. So, the computer would interpret and write down the notes and timings it heard, but obviously the results are very unpredictable. It was funny, and we would wonder how the software could get to this or that, but it was an inspiring starting point. Other times we transcribed it ourselves by listening to the pitches. For this project, we tried to transcribe it only into the language of the piano in terms of rhythmical gestures, pitches and some timbres.

Now we are working on a notation project, which has a different approach. Basically, we were starting from different patches on the Buchla which all take the theme of natural soundscapes, for example mimicking bird-like sounds. Then the next step is the notation. We came up with a very visual notation which is based on the look of the Buchla, and the fact that it has three different kinds of signals, we use different colors for each of those. It is a notation that starts from a precise place, but it becomes something which is not very detailed, and it is open for interpretation. It consists of signal and patch information using a basic print on paper and then additional transparencies on top to represent the patch. We hope to send it to other musicians, inviting them to give us their interpretations, and it will be interesting to see what kind of different results to get.

Christopher: The notation is a bit like a puzzle. It can work on any system, but because you separate the signals on this Buchla, you have to look for something in the other systems that have a correlating input and output. So, everybody will get a completely different result for sure. It’s interesting because Buchla made a language for people that in some way is guiding their way of making music, and so the question is: Is Buchla a composer in that sense? Is this notation of the patches also a way of composing? You will have no idea what other people are going to come to, and you can only have so much influence on what they make. I find this very interesting to think about.

Are you planning a CD or a concert with the second project, too?

Nicoletta: We are planning video recordings of our initial patches with the soundscapes. We hope to have a digital version of the scores, and maybe also a printed version which is more beautiful to have and play with. We are also very fascinated with the idea of writing a piece of software. We started into the world of synthesizer sounds through a free open-source software. There are no open-source resources for this Buchla type, so we were thinking of setting up a website that is based on this Buchla to play virtually.

Is it your first time in Austria?

Christopher: No, but the first time we’re here together.

Nicoletta: Austria has been really important to me. I had my first real contact with contemporary music when hearing “Kontakte” from Stockhausen in Verona in Italy, but the next one was in Graz at impuls Festival. It was the first time I was in contact with this contemporary community which was mind-blowing. I saw that contemporary music is alive, that there are still living composers. We are very happy to be back in a country where the music scene seems to be so active.

Chris was in Austria about 4 years ago at Klangspuren Festival. It’s great to be staying here so long. Austria is so close to Italy but so different. Everything, the food…

Christopher: And the contemporary music scene here is so open.

Nicoletta: Yes, also here in Krems. The scene here is very open to northern and eastern parts of Europe which is totally ignored in Italy in the music and art scene. Of course, the pandemic is a very special situation. We don’t really know what Krems is like in normal times.

Christopher: Yes, we can only imagine. But we’ve been around a bit in Krems and we went to Dürnstein with the bike. It’s still very nice.

Thank you very much for the interview!

- A documentation by Passepartout Duo about their work in Krems and announcement of their new EP

In cooperation with AIR – Artist in Residence Niederösterreich and Klangraum Krems Minoritenkirche.

Website of Passepartout Duo