Online anniversary concert

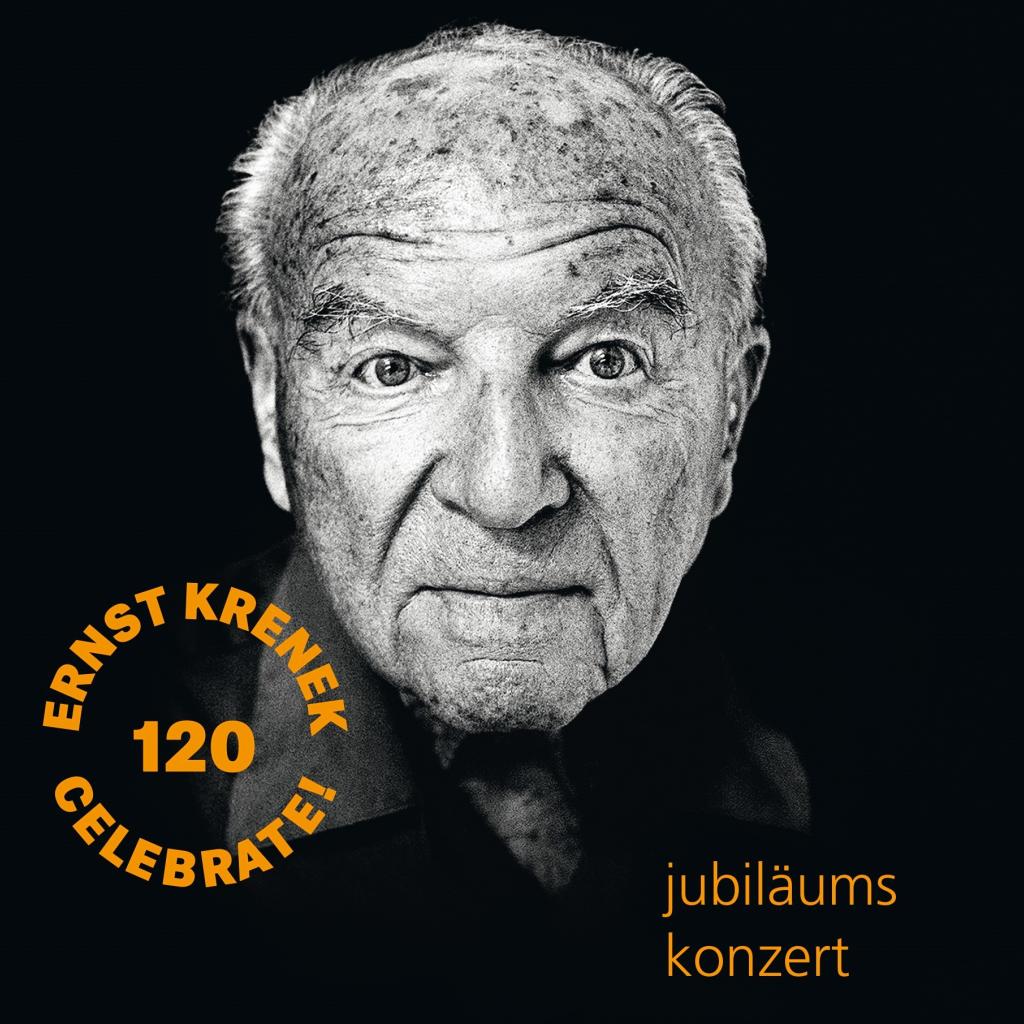

120 years of Ernst Krenek - 250 years of Ludwig van Beethoven

Welcome to our online anniversary concert in honor of Ernst Krenek’s 120th birthday and of Ludwig van Beethoven’s 250th birthday.

Due to corona, the concert on November 5, 2020 at Minoritenkirche Krems could not take place with audience. We are happy, however, to present you this online concert. Until December 31, 2020 you are welcome to hear two extraordinary string quartets by the two composers.

Program

Welcome speech

Martina Pröll, Alethea Neubauer und Clemens Zoidl

Management team of Ernst Krenek Institut Private Foundation

Greeting

Minister Christiane Teschl-Hofmeister on behalf of the governor Johanna Mikl-Leitner

Concert

Ernst Krenek

String Quartet No 7, op. 96

Ludwig van Beethoven

String Quartet No. 12, op. 127

Online Concert

Das Konzert ist leider nicht mehr verfügbar.

With kind permission of Universal Edition and G. Henle Verlag and with kind support of Land Niederösterreich and Bundesministerium für Kunst, Kultur, Öffentlicher Dienst und Sport.

Introduction to the concert

“The dignity of composing as manifestation of simple human dignity”

Hearing in the mind

Krenek’s day of birth was 120 years ago, and 120 years also separate the two string quartets juxtaposed in this concert program. One hundred and twenty years of musical history are reflected in a clearly audible tonal-aesthetic distance – or at least it seems so at first impression. Thereby, the two composers are closer together than one might initially suppose.

In several of his string quartets (so, too, in the Seventh), Krenek made reference directly to Beethoven, and also analyzed his works in lectures and essays. Moreover, Krenek understood a specific technical idea in Beethoven’s late string quartets as a vision that was only to be realized in twelve-tone composition. And even Krenek’s understanding of composing as a creative act displays a broad consensus with his 130-year-older colleague.

An apparently superficial similarity is that neither composer made use of external hearing impressions in the creation of their works. In the case of Beethoven, it would be easy to understand this as an involuntary consequence of his deafness. Yet, as Krenek stressed in a lecture about working creatively in music, the craft of the “professional composer” distinguishes itself in that it is not dependent on improvisatory trying out “on the piano,” but, on the contrary, that this is a waste of energy and distracts the creative intellect more than it stimulates. In his composition teaching at Hamline University in Minnesota, Krenek accordingly attached great importance on the creative work of his students within the framework of musical imagination.

In any case, this hearing in the mind led both works – as different as they may be in terms of their superficial-aesthetic sound impression – to great individuality and originality.

Logical construction and warmth of expression

Krenek wrote his Seventh String Quartet in the cold winter months of 1934/35 in Minneapolis, when he was chairman of the music department of Hamline University. During this time, Krenek further evolved his own method of handling twelve-tone composition as developed in the works of Schoenberg and his circle of students. He was inspired in this, on the one hand, by his occupation with the counterpoint of Renaissance music as a result of his teaching and, on the other hand, from the need to relax the methodic rigor of composing with twelve-tone rows in favor of greater freedom and expressiveness. Without having to give up the structural qualities of the row principles, he found the sought-after flexibility in a segmentation of the twelve-tone rows. In the Third Piano Sonata, which numbered among Glenn Gould’s favorite compositions, Krenek formed his musical material out of a division of the twelve-tone rows – in his Seventh String Quartet he went a step further. Even if the “germ cell” of his quartet is a twelve-tone row (d–a–g-sharp–c-sharp–b–d-sharp–f-sharp–c–b-flat–g–e–f), it is never used in this basic form: the row is divided into four three-tone motifs, whose number is expanded through rotations of the row’s tones and other permutations into an abundance of motifs that are related to one another. This allows an extremely expressive freedom in the shaping of the themes in spite of a simultaneously very compact, precisely crafted structured form that holds all five of the work’s movements in relationship with each another. Krenek, who at times was inclined toward harsh self-criticism, cherished exactly these qualities in this work: “I find that in the Seventh Quartet, I achieved the balance of logical construction and elasticity, the exactness of the work and warmth of expression to which I have endeavored during my entire career” (Memoirs, 1949).

As already in earlier works, Krenek adopted from Beethoven’s String Quartet op. 131 the principle of movements that are strung together and segue uninterruptedly. Two contrasting subjects are introduced right at the beginning and further developed during the course of the first movement. The second of these subjects establishes the lyrical-expressive character of the second movement. Great density is attained in the central third movement: an elaborate fugue with three subjects, which were all developed out of the preceding subjects, are heard during the course of the fugue both in the basic form as well as in inversion, and combine at the end of the movement in a dramatic climax. The fourth movement is a calm transition to the fifth movement, which in the form of a rondo takes up the subjects of the preceding movements, in this way lending the work a cyclical form.

In view of the high regard that Krenek personally had for this work, the dedication seems to suggest more than a mere formal gesture of affection: Dedicated in Gratitude to the Vivifying Spirit of my American Students.

Not for donkeys

As the first of the group of so-called late string quartets, Beethoven’s op. 127 proves to be the most traditional of these works, which for their groundbreaking and, for the contemporary listener, challenging modernity received already early on a notorious reputation in the repertoire of classical-romantic chamber music. The String Quartet in E-flat Major was largely written in 1824 as a commission from Russian prince Nikolai Golizyn, who was living in Vienna. Sketches, however, reach back to 1822. They show that in this work Beethoven already played with the idea of bursting open the traditional four-movement form. But ultimately, he left it at the fast–slow (variations)–scherzo–fast sequence of movements that he employed, for example, already twenty years earlier in his symphonies.

However, the conventional structure proves to be only the external framework of a music that in its demands reached the very boundaries of contemporary listening habits. Already before the premiere, Beethoven worried whether the Viennese would like his newest work. Ignaz Schuppanzigh, the first violinist of the string quartet presenting the premiere, wanted to dispel Beethoven’s concerns. Beethoven’s conversation books, which as invaluable historical sources have preserved at least a part of his conversations, provide Schuppanzigh’s words about the part of the audience that would reject Beethoven’s ambitious music: “There are only a small number of donkeys who will make fools of themselves.” And with a hefty eighteenth-century profanity, he added the recommendation: “Shit on them.” (The conversation with Beethoven then probably led in a different direction – the next entry reads: “This pastry cannot be made so quickly at home.”)

According to a report about the premiere in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung from March 1825, the audience’s opinion was “divided.” Schuppanzigh’s poor execution – according to contemporary reports – probably also contributed to this. Later performances with other violinists and string quartets were better able to show the high quality of the composition, and the work very quickly found admirers. The lyrical-cantabile Adagio of the second movement was performed, in an arrangement for voice, at Beethoven’s funeral ceremony.

As stated at the beginning, Krenek also numbered among Beethoven’s admirers. To be sure, his compositional path, after the phase of free twelve-tone composition at the high point of which the Seventh String Quartet was composed, found its way to the constructive rigor of serialism, from where Krenek could “no longer see a model in the classical logic of emotionally motivated tonal structures.” But what remained for him at this phase of occupation with Beethoven’s string quartets, and certainly what expressed his unwavering high regard for this music, was “a feeling for the dignity of composing as manifestation of simple human dignity.”

Clemens Zoidl

Minetti Quartet

Maria Ehmer, Violin

Anna Knopp, Violin

Milan Milojicic, Viola

Leonhard Roczek, Violoncello

Since its nomination for the "Rising Stars" cycle of the "European Concert Hall Organisation" in 2008/09, the Minetti Quartet has repeatedly performed in the most prestigious concert halls in Vienna, Berlin, Cologne, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Stockholm, Brussels, London etc. Invitations to famous chamber music festivals have also taken the quartet to North, Central and South America, Australia, Japan and China. Many concerts were recorded and broadcasted by international radio stations.

The name "Minetti Quartet" refers to a play by the writer Thomas Bernhard, who lived in Ohlsdorf in the Salzkammergut region, where the two violinists of the quartet also grew up.

Chamber music partners include Fazil Say, Till Fellner, Jörg Widmann, Paul Meyer, Sharon Kam, Thomas Riebl, István Vardai, Camille Thomas, Alois Posch, soloists of the Vienna and Berlin Philharmonics and the Mandelring Quartet. The quartet has performed as soloists with the RSO Vienna and the Bruckner Orchestra Linz.

The Minetti Quartet is the winner of numerous international chamber music competitions (Schubert Competition, Haydn Competition) and also received the Austrian "Großer Gradus ad Parnassum Preis", the starting scholarship of the Austrian Federal Ministry as well as the Karajan Scholarship.

The Austrian National Bank lends the quartet two violins by G. B. Guadagnini ("Mantegazza" 1774 and the "ex Meinel", 1770-1775) and a violoncello by G. Tononi (Bologna, 1681). Milan Milojicic plays on a viola by Bernd Hiller (2009).

Last but not least

How did you like the concert? We appreciate your feedback!